Detainees memorialized at old INS building

Walking into the Inscape Arts and Cultural Center didn’t feel quite like I thought it would. The building looks more like a school or a train station than the former home of United States Immigrant Station and Assay Office. But that’s exactly what it is.

This past Sunday, Dec. 7, Inscape opened “Voices of the Immigration Station: 72 Years of History on Five Floors,” a permanent exhibit documenting the troubled history of the building, in partnership with the Wing Luke Asian Museum of the Pacific American Experience. The office, also known as the INS building, opened in 1932 as a stop — sometimes a permanent one—for new Americans.

Droves of people once waited outside of the building, hoping they could become American citizens, dreading the possibility of being deported back to the countries from which they fled. Because of this, the INS building became known as Seattle’s Ellis Island.

In the exhibit, voices of immigrants and refugees are finally memorialized, said Jay Stansell during the exhibit’s opening reception. Stansell is an assistant federal public defender who once represented detainees in the INS building. The Inscape lobby, which once served as the building’s front desk area is now a small art gallery and museum dedicated to explaining the history of refugees and immigrants in the United States.

“We rarely bring [the conversation] to the present to talk about [what’s happening] today,” Stansell said. “The building is now a positive place of creativity … but it bears noting that in place of this, [the government] made a high-tech deportation facility in Tacoma.”

The INS building closed in 2004 when the Northwest Detention Center, a privately-owned facility, opened just outside of downtown Tacoma.

“It’s important to tell the history through art because art can touch on those harder stories,” said Stacey Fischer, founder and creative director of Buoyant Design, housed in the Inscape center. Fischer helped design the three-dimensional elements of the exhibit, including informational placards and historical timelines.

One of the installations is by comic artist * Eroyn Franklin, who turned the oral histories of two former detainees into “Detained,” a double-sided panoramic graphic novel. On the first side, readers follow Many Uch, a Cambodian-American immigrant, who was detained at the INS near the end of the facility’s operation. The other side examines the Northwest Detention Center through the eyes of Gabriela Cubillos, a Mexican immigrant, who was once held at the prison.

“When [the building] was empty, it still felt full of people,” said Franklin, who worked with The Seattle Globalist, formerly The Common Language Project, to produce * “Between Worlds/Behind Bars,” a four-part radio series exploring immigration in Washington.

And the building is full of people. After some renovations in 2008, the historic Inscape building was converted into rented studio space for more than 100 local artists. Where there were once towering filing cabinets documenting each person who passed through INS, there are now portraits and abstract artworks.

“Artists came [into Inscape] to help breathe new life into the building. The eagerness of the tenants to want to know the history helped with this partnership,” said Cassie Chinn, deputy executive director at the Wing Luke Museum. “The revitalization of the neighborhood is important for us.”

While colorful canvases and sculptures line five stories of the building’s hallways, scars of the building’s darker past still remain. The basement, once used as booking facility, still bears the painted handprints where INS officers routinely searched detainees. There are spackled-over holes that once bolted a cage-like enclosure to the wall, which was used for interviewing detainees. A placard on the third floor notes that a hallway of studios were once solitary confinement cells that echoed with the screams of inmates, some of whom were mentally ill.

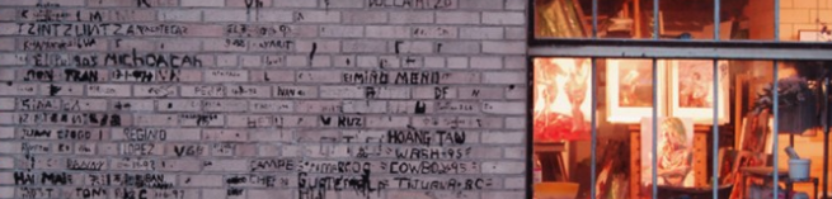

The rooftop recreation courtyard left me feeling particularly winded. After passing through the heavy metal door, your eyes are immediately drawn to the words on the walls. The detainees’ words are etched in melted tar, spelling out their names or from where they emigrated, as if to say “I was here.”

The words, some probably more than 50 years old, stare out at CenturyLink field, out into Seattle. It’s from this courtyard, about two stories up, that one East African detainee fell to his death during an attempted escape.

The building has a bit of an eerie feel to it, to say the least.

But today, the Inscape building is full of life and good energy. There are artists roaming the building, creating dreamlike spaces out of rooms that were once a living nightmare for the people who were held there.

Ultimately, the center is a place for reflection through art. It is a place for us to remember our history and commit to the continued effort to strengthen our community.

*Editor’s Note: Eroyn Franklin’s work “Detained” was done in collaboration with the Globalist, though not published as part of our related series, “Between Worlds/Behind Bars.”

This article was originally published in the International Examiner.

Recent Comments